A former Oklahoma City police officer faces federal witness tampering and mail fraud charges for teaching people how to pass the polygraph test. Doug Williams was indicted last year after an undercover sting operation and his trial begins Tuesday in the Western District of Oklahoma Federal Court.

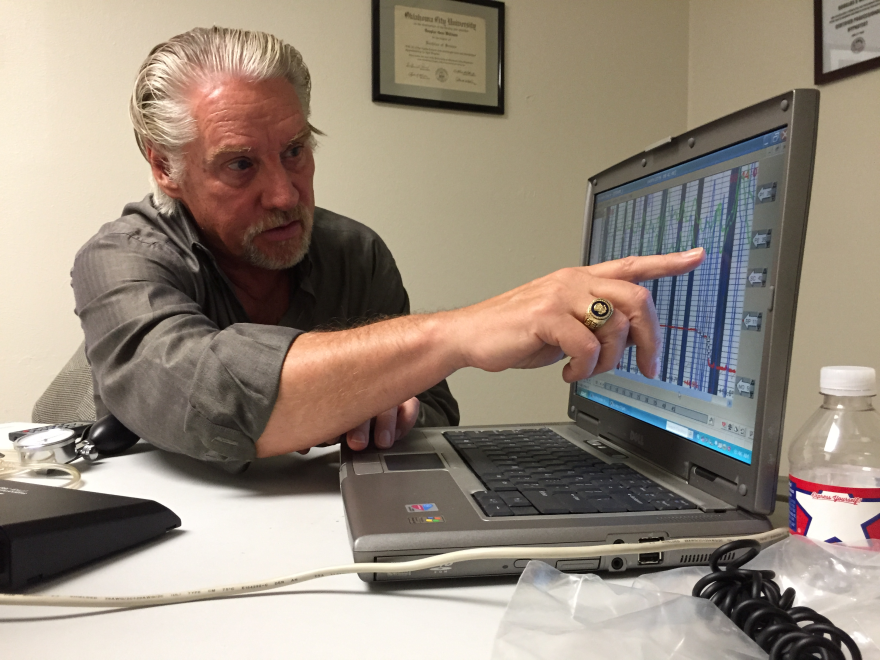

Williams meets clients at his tiny, spartan rented basement office on Main Street in Norman, where he charges $1,000 for one-on-one training sessions.

The polygraph machine measures breathing, blood pressure, heart rate and sweat. Williams said those responses sometimes indicate deception, but they can also come from other variables like stress, nervousness or something as simple as the tone of the examiner’s voice.

“We have a problem with the basic premise of the polygraph in that it does not detect deception,” Williams said. “It detects a physiological response to a stimulus, and that stimulus may be the act of lying but it’s just as likely that it’s something else.”

Williams was an interrogator with the Oklahoma City police in the 1970s. The polygraph was a big part of his job then. But for the past 36 years, he’s been a fiery critic of the machine he calls “a psychological billy club.”

“What we have here is a machine that can watch you breathe, watch two fingers on your right hand sweat and watch your heartbeat,” Williams said. “And they have the audacity to say that by monitoring these physiological reactions whether or not you are telling the truth.”

Federal law prohibits the private sector from using the polygraph and courts almost never accept polygraph evidence. But governments still use the test for job applicant screening, internal investigations and security clearances. And that’s what got Williams in a lot of hot water.

In a sting operation, two undercover federal agents asked Williams for training. One posed as a Department of Homeland Security agent under internal investigation for smuggling, while the other said he was applying for a Customs and Border Patrol job. According to the indictment, both men admitted they would lie, yet Williams reluctantly agreed to train them.

Williams insists he told neither man to lie.

“I thought the second one was just nuts. I just literally thought he was a mental patient. The first one, I thought they already knew what he was accused of having done ... and he was just basically trying to keep from getting accused of something else other than that,” Williams said.

Read the indictment against Doug Williams. Warning: contains graphic language

The polygraph machine is unreliable, according to Art LeFrancois, a law professor at Oklahoam City University.

“There’s been legislation at the national and state levels governing the use of polygraphs also because of their inherent unreliability,” LeFrancois said.

A 2002 report by the National Academy of Sciences found the polygraph is based on weak science, and recommends the government stop using the machine on prospective or current employees due to its unreliability which has led to countless false positives that disqualify people from jobs. But they are still commonly used.

LeFrancois was initially concerned when he heard about Williams’ case because it sounded like the government was trying to squash attempts to teach people how to avoid false positives. But he said the evidence in the government’s indictment alleges Williams may have crossed the line.

“It does look as though there may have been an effort to knowingly aid people in their efforts of deception,” Lefrancois said.

John F. Sullivan was a polygraph interrogator at the CIA for 31 years. A properly done polygraph test, he said, is the best personnel security device available.

“I’ve caught too many liars to say it doesn’t work and I’ve been beaten enough times to know it isn’t perfect,” Sullivan said. “But to categorically state it’s absolutely worthless is nonsense.”

Sullivan said the machine isn't the problem at the CIA - it’s the interrogators. Soviet spy Aldrich Ames passed two polygraph tests and after he was exposed in 1994, polygraph examiners were too paranoid to pass people. The number of false positives increased.

Even though he believes the polygraph machine is still useful, he thinks it’s a mistake for the government to target Doug Williams.

“I don’t agree with Mr. Williams’ ability to teach people how to beat the polygraph test. But I also think he has a right to do it. As a polygraph examiner, maybe he makes my job a little bit harder but I really don’t think so,” Sullivan said.

Williams isn’t the first polygraph countermeasure trainer to draw the Department of Justice’s attention - Chad Dixon pleaded guilty in 2012 after a similar undercover operation in Indiana. He served eight months in prison.

For Williams, he feels like Don Quixote tilting at windmills. He sees the polygraph as an injustice that has ruined careers and lives, but change is slow to come.

“I guess that’s what we do in this country,” Williams said. “If you have a valid argument against something that the government is using and you protest loudly and longly against it, then you get thrown in the federal prison.”

Williams faces five counts of mail fraud and witness tampering, and each carries a maximum sentence of up to 20 years in prison, and a $250,000 fine.

-----------------------------------------------------------

KGOU relies on voluntary contributions from readers and listeners to further its mission of public service to Oklahoma and beyond. To contribute to our efforts, make your donation online, or contact our Membership department.