After 23 years in the child-care industry, Laura Hatcher is edging toward a decision she doesn’t want to make.

The 51-year-old Antlers resident runs one of the four licensed day-care facilities in Pushmataha County in southeast Oklahoma. But she questions whether she can keep her doors open beyond another year or two because running the business is getting more expensive and difficult.

“It’s a struggle and I’m working 11, 12 hours a day,” she said. “If it continues the way it is, I’m not going to be able to keep going.”

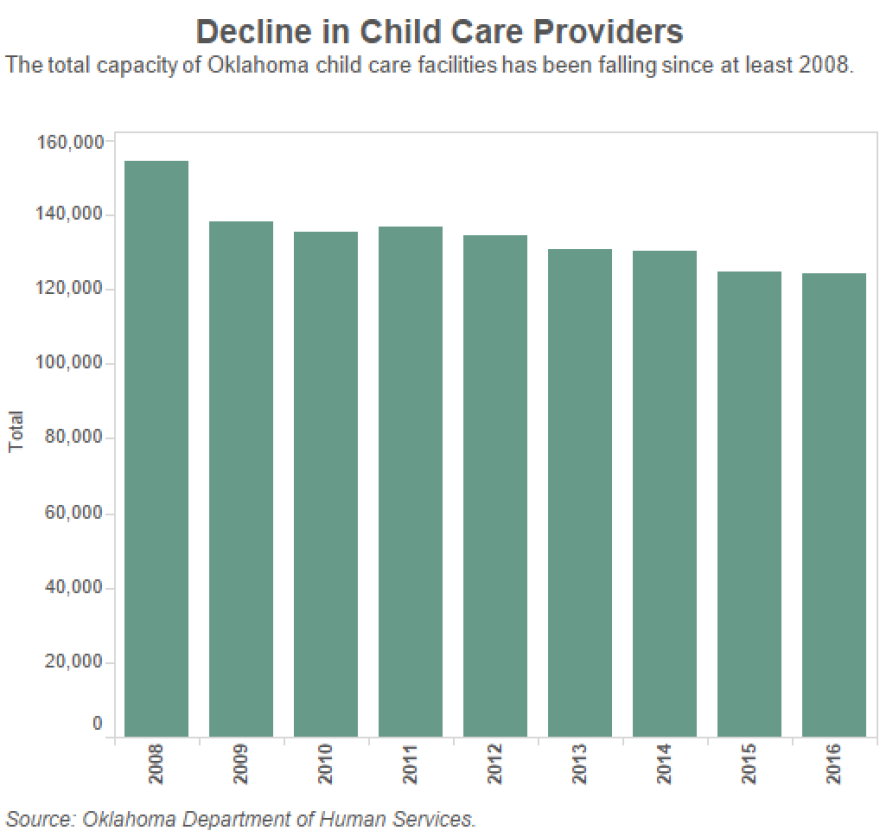

Hatcher’s problem reflects a larger trend of rising financial pressures that have caused increasing numbers of child-care facilities across Oklahoma to close their doors. Since 2008, the number of child-care homes or centers has declined by 34 percent, to 3,409, and the number of spaces in these facilities has dropped by 20 percent, according to Oklahoma Department of Human Services figures.

The decline is placing a burden on parents because it means fewer choices for child care and, with a tighter supply, higher prices.

A 2015 survey released earlier this year by DHS found that 44 percent of parents who were looking for child-care experienced difficulty during their search – up from 31 percent in 2013 and 22 percent in 2011.

The reasons for the decline are somewhat in dispute. Child-care providers attribute it to a tightening of state regulations in an already highly regulated state; government aid that lags increasing costs, and difficulty in recruiting and retaining workers.

State officials, however, question providers’ assertion that regulations have become too burdensome; they suggest other factors are at work.

“We are very proud of our standards and oversight here in Oklahoma,” said Lesli Blazer, director of child care services for the Department of Human Services.

She pointed instead to another problem affecting the industry here and nationwide: low pay for child-care workers, which has led to staffing shortages.

“It’s a really hard job and the pay is low,” she said.

Child-care providers and advocates say parents who are patient, determined and oftentimes lucky can still usually find care, especially in more populated areas.

But Paula Koos, executive director of the Oklahoma Child Care Resource & Referral Association, said finding care often means paying more or compromising on location, quality or what type of day-care center a parent prefers.

It is especially a challenge for parents looking for after-hours care, help with special-needs children or available spots in rural parts of the state, Koos and child-care providers said.

“In certain counties in the state it is virtually impossible to find care,” Koos said. “In some counties there might just be one facility in the entire county. Every child needs care, and if the number continues to slide, eventually we won’t be able to find care for anybody.”

Low-Profit Industry

A report released in July by Child Care Aware of America found that to a certain degree in every state, access to quality child-care programs is “hard to find and difficult to afford.” The report noted that many providers operate on low profit margins, which increases their vulnerability to market or regulatory changes.

But many Oklahoma child-care providers argue that unlike in some other states, Oklahoma is over-regulating the industry and making it too hard for some to stay in business.

Oklahoma ranks among the most stringent states in the country for standards and oversight of child-care centers, according to Child Care Aware of America, which tracks child-care trends.

Rikki Cosper, head of the Licensed Child Care Association of Oklahoma and director of the McGee Bright Start Early Education Center in Norman, said she and others support common-sense rules that ensure children’s safety.

But Cosper said facilities often are not given enough flexibility when trying to follow the rules or abide by constantly changing staffing mandates and other requirements.

As a result, many providers are constantly worried about getting hit with violations, which can hurt their reputation, make them ineligible to accept subsidized care or lead to revocation of their license, Cosper said.

“I think it just gets to a point where it’s not worth it,” she said. “Most people in child care are not in for the money. It’s just not worth all the stress.”

In 2008, the state imposed tougher regulations in the wake of high-profile incidents, including the death of a 2-year-old at a Tulsa child-care home. The changes included:

- Instructing DHS to maintain a publicly accessible online database of child-care facilities, along with their quality rating and any complaints or inspection violations.

- Mandating background checks for child-care facility owners and employees.

- Increasing or setting new training and other licensing requirements.

- Requiring facilities to notify parents of a failure to maintain liability insurance coverage of at least $200,000 for each occurrence of negligence in which a child is injured while on the premises.

At the start of this year, DHS put in place a series of new regulations over objections from the Licensed Child Care Association. Those include new teacher qualification rules, medication dispensing standards and removal of new hires’ ability to work under supervision while their background check is being processed.

The association and dozens of providers signed letters asking Gov. Mary Fallin and the Legislature to revoke the rules.

Rep. Josh Cockroft, R-Wanette, authored a bill to revoke them but it didn’t advance out of committee. He and other lawmakers did successfully lobby for an interim study on child-care licensing rules, to be held later this year.

State officials defend the state’s regulations, both old and new ones.

“Our focus is on the health and safety of the children,” said Blazer, of DHS, adding that the rules were created in close collaboration with child-care providers.

Regarding the decline in facilities, she noted, “Since the start of 2016, we really haven’t seen a decline in providers, so I don’t think you can tie the rules to the decrease.”

She cited instead the low wages and staffing shortages.

According to a report by the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment at the University of California, the average child-care worker in Oklahoma makes $8.90 an hour – the eighth lowest rate in the country and more than a dollar below the $9.77-per-hour national average.

Lagging Subsidies

Kathy Cronemiller, president of the Oklahoma Child Care Association and owner of six child-care centers in the Oklahoma City area, said the low pay is partly an offshoot of a larger problem: The state’s child-care subsidy benefits, a main source of income for many facilities, have been stagnant for years.

The benefit program uses state and federal funds to pay all or a portion of child-care costs, depending on the parent’s income. It also requires the parent to choose a facility with a one-plus star or higher quality rating and be working, attending school or taking training classes.

For those with one child in care, families only began to qualify if their monthly household income is lower than $2,426, which equates to wages of less than $14 per hour. Such families would pay a monthly co-pay of $189, according to a state schedule that hasn’t been updated since 2008.

“Almost no one can qualify anymore,” Cronemiller said.

As regulations drive operating costs up, Cronemiller said, it becomes harder to survive, unless a center is already established.

“We’re basically at a stalemate because we are making the same amount of money with no (subsidy) increases, so we can’t give our employees any money and we lose our employees to other positions,” she said. The result is that “centers are going to raise their rates where parents just can’t afford it.”

Oklahoma’s budget situation isn’t helping.

Because of last fiscal year’s budget shortfall, DHS was forced to freeze applications for its subsidy program for two months. In August,the agency said it plans to reduce its already limited funding for training, scholarships and professional development for child-care workers.

The department also plans to reduce staff in child care services, saying in a news release that this will affect “oversight and quality of child care homes and facilities, which may result in safety issues for children.”

Further cuts are possible because the agency faces a shortfall of more than $55 million for the 2017 fiscal year.

Tough Decisions for Parents

Bethany Soler, a Tulsa resident and working mother, had her third child in April.

She knew to start looking for day care while she was pregnant. After encountering centers with long waiting lists and unaffordable prices, she settled on a new center run by friends. Then her child kept catching colds at the center.

Soler gave up and began paying her mother to drive every day from Broken Arrow to Soler’s home in west Tulsa to stay with her child while she was at work.

“I would be paying as much as mortgage just to have one infant in day care,” Soler said. “… “There are no easy choices.”

Kathy Williamson, who runs Cross Creek Early Learning Center in Jenks, also sees parents constantly making sacrifices because they can’t find affordable care. In her 90-capacity center that serves infants through 5-year-olds, she said conversations with parents get difficult when she informs them her wait list is between a year and 18 months.

“On a weekly basis we have parents that hang up on us or get frustrated with us asking what they can do to just get into a center,” she said. Some have quit their jobs to stay home because they can’t find child care, she said.

Koos, of the resource and referral association, said more affluent parents have fewer problems. If there are no openings in nearby centers, they may turn to more expensive care provided by an outside individual or service in the child's home - which is exempt from licensing rules.

She added she worries most about families who make just above the subsidy’s salary threshold. Those parents often must choose between quitting a job or relying on a patchwork support system of family, friends and babysitters to watch their children.

“And that is hard on the kids and it is hard on the parents,” Koos said.