The Catholic church will beatify a priest from Okarche, Oklahoma this weekend. Three assailants murdered Father Stanley Rother in Guatemala in 1981. Pope Francis declared last year that Rother is a martyr, setting the stage for him to possibly become a saint.

Wayne Ludwig stands outside Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Okarche, Oklahoma, following a Saturday afternoon mass. Ludwig grew up down the road from Father Stanley Rother in this postcard-flat farming town of about 1,200 people, northwest of Oklahoma City.

“I remember when he came up from Guatemala. One time he came up and had little old red pickup and had all kinds of old antique farm machinery and took off back down there for those people to use. That’s just kind of the guy he was. He just kind of helped as he went,” Ludwig said.

Stanley Rother had farming in his blood. In high school, he was president of the local chapter of Future Farmers of America.

His sister, Marita Rother, is a nun with the Adorers of the Blood of Christ in Wichita. She said most people in town expected him to eventually run the family farm.

“We had a pastor at the time who spent quite a bit of time coming up to people's farms, helping with the farming, getting on a tractor and getting his hands dirty,” Marita Rother said. Her brother saw this priest as a role model.

“And he thought, well, if I can be a priest and do some of this, being the farmwork, of course, maybe that would work,” Marita Rother said.

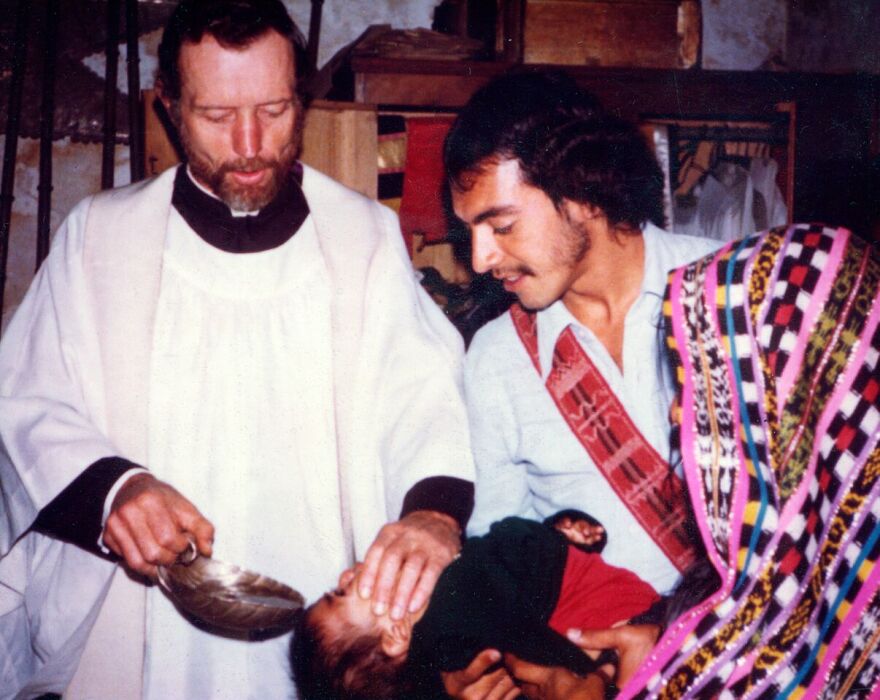

Stanley Rother went to seminary in San Antonio, Texas but he struggled with Latin. He failed his first year and was sent home. He later finished seminary in Maryland and was ordained. In 1968, the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City sent Rother to Guatemala, to serve as a missionary in the community of Santiago Atitlan. Even though he struggled with Latin, Rother learned Spanish and the local Mayan language, Tz’utujil.

Among the people he worked with was Juan Pablo Ixbalan.

Speaking with KGOU on Skype with a Tz’utujil translator, Ixbalan says Rother gained trust from his parishioners by speaking the local language, and he was given the name A’plas. He started a radio station, a health clinic and nutrition programs. He introduced farmers to new crops like wheat, carrots, tomatoes, radishes and other vegetables.

Santiago Atitlan was a poor community, and the violent Guatemalan Civil War took a heavy toll. Guerilla fighters hid in the surrounding mountains and tried to recruit town members. Government soldiers occupied Santiago Atitlan and kidnapped or killed anybody who was suspected of fighting for the rebels. Rother’s church was a sanctuary for those who feared for their life.

Ixbalan says Father Rother gave watches to farmers. He told them to leave the fields by four o’clock and go home, otherwise government soldiers would get suspicious they were working with the rebels. He also invited soldiers to come to mass.

In letters home, Rother wrote, “Shaking hands with an Indian has become a political act.”

Maria Scaperlanda worked on the Oklahoma City Archdiocese historical commission that petitioned for Rother’s case for martyrdom, and she’s written a biography about him. She says the Guatemalan government treated anybody who was helping the poor as a possible guerrilla sympathizer.

“The poor were the ones that were being labeled as the ones causing trouble for the country,” Scaperlanda said.

Rother would personally search for the bodies of disappeared parishioners. He set up a fund to help the widows and children of victims - an act he knew the government would consider subversive. He ended up on a death list.

“It wasn't unusual for a different priest to be on death list, but being an American on a death list was a big deal,” Scaperlanda said.

Rother briefly left Guatemala and returned to Okarche. But he was restless. He wanted to be with the imperiled community he had served for 13 years.

“One of the images that he used a lot in his letters was to say that ‘The shepherd cannot run at the first sign of danger.’ And in another letter he said, ‘The shepherd cannot leave his sheep’,” Scaperlanda said.

“I had a good idea by that time in our lives that there was no way to I would be able to convince him not to go,” his sister, Marita Rother, said. “But you know, you try. And the last time that I spoke with him, it was just a matter of just saying, you know, are you sure this is what you need to do? And he said, ‘Well, I think this is. I know it is.’”

Stanley Rother returned to Santiago Atitlan. Months later, three men broke into the rectory. They shot and killed him. The following day, people filled the plaza outside the church. Community leaders in Santiago Atitlan had one request: His body could be buried in Oklahoma, but they wanted to keep his heart. His family agreed. His heart is still in the church.

Pope Francis declared Stanley Rother a martyr last year. His beatification ceremony on Saturday is the final step before possible canonization as a saint.

Oklahoma City Archbishop Paul Coakley says beatification is a formal declaration that someone lived a noteworthy, heroic, virtuous life that is worthy of imitation.

But Coakley says the road to sainthood isn’t over yet.

“Quite literally it will take a miracle because that's what the church requires for somebody to be canonized as a saint,” Coakley said.

Archbishop Coakley says a miracle usually comes by way of a person with an incurable disease who has exhausted medical care and asks for intercession from somebody like Stanley Rother. If the favor is granted and the disease is cured, a medical tribunal will investigate.

“If there is no medical explanation, scientific explanation for the healing that the person has experienced and received, applying the very rigorous medical tests to that person, it could be declared a miracle. And that's what will be required for Blessed Stanley to become St. Stanley,” Coakley said.

Juan Pablo Ixbalan, the Guatemalan man, says it would be an honor for Rother to be canonized. But to him, personally, Rother is already a saint, for everything he gave to his community.

Rother’s beatification ceremony will be held at the Cox Convention Center in Oklahoma City on Saturday, September 23 at 10:00 a.m.

As a community-supported news organization, KGOU relies on contributions from readers and listeners to fulfill its mission of public service to Oklahoma and beyond. Donate online, or by contacting our Membership department.